This guide provides a general overview of the main legal considerations pertaining to public and private company M&A in Canada. Among other things, the guide reviews the duties and obligations of directors and officers and covers both unsolicited and negotiated transactions.

M&A transactions in Canada require consideration of both federal and provincial/territorial laws. Canada’s provincial and territorial governments have jurisdiction over property and civil rights within each of their territories, and therefore elements such as contract law, real estate/property law, and labour and employment generally fall within their jurisdiction. Securities regulation also falls within provincial jurisdiction, which contrasts with other nations having a centralized, national securities regulator (the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, for example). Although securities laws have become more harmonized over time, differences remain that often require careful consideration when reviewing for compliance or the possibility of exemptions. An example includes French document translation requirements in Québec. In the public company context, the policies of the applicable stock exchange on which a company’s shares trade will also apply to M&A transactions, particularly when they involve the issuance of securities of the purchaser.

This guide is intended for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Information is current to August 2025, and is based on the laws of British Columbia and federal laws applicable therein. Laws of other Canadian jurisdictions may differ, in some cases significantly. The distribution of this guide to any person does not contribute to the creation, continuation or renewal of a lawyer-client relationship with Kornfeld LLP or any related person.

In the context of privately held business entities, acquisitions generally proceed through either share purchase transactions, asset purchase transactions or statutory amalgamations. If acquisitions utilize shares or other securities of the acquiror as consideration, securities laws may apply, as well as additional tax considerations.

In a cross-border context, it is generally to the advantage of a foreign purchaser to use a Canadian acquisition vehicle when acquiring a Canadian target, which two companies are then often amalgamated post-closing. This structure is designed to ensure that the purchaser holds shares with high paid-up capital which can be distributed out on a tax-free basis (versus dividends, which would be subject to withholding tax). The amalgamation would also allow the expenses paid to finance the acquisition to be deducted from the target’s business income.

In cross-border transactions, “exchangeable share structures” are also often implemented when the purchaser wishes to use its own shares as consideration. Applicable Canadian tax law permits a deferral (or rollover) of capital gains tax only if the seller receives shares of a Canadian corporation. Where Canadian shareholders of the target may be subject to significant capital gains upon the sale, an exchangeable share structure may be preferable in order to defer their capital gains tax exposure until such time as such holders receive cash or liquid stock in order to fund such tax. In essence, the foreign purchaser incorporates a Canadian subsidiary that will issue shares that are exchangeable into the purchaser’s shares, where these exchangeable shares are the economic equivalent of the purchaser’s shares (for example through dividend entitlements and voting rights).

In the public company context, when the structures mentioned above are not available, acquisitions may also proceed by statutory plans of arrangement or take-over bids.

Share Purchase Agreements

Overview and General Utilization

Share purchase agreements involve a purchaser who buys all (or a majority) of the target company’s voting shares or ownership interest from the target company’s shareholders. This generally means that the ownership of the target company’s assets, rights, liabilities and obligations remains with the target. While the purchaser may receive the benefit of the target company’s assets and rights, it will also take on all of the liabilities and risks, including potentially those which are unknown at the time of the share purchase, unless the agreement requires those to be paid out by closing.

Advantages

A share purchase can be advantageous to a potential purchaser in the following ways:

From the perspective of the seller, a share purchase could offer the following benefits:

From a tax perspective, a seller of its shares in a Canadian company will derive tax advantages since the transaction will generally give rise to capital gains, which are effectively taxed at half the rate of ordinary income, any may be able to rely on a sizeable one-time exemption from capital gains tax if it is a Canadian resident and meets certain conditions. Additionally, if the consideration includes shares of a purchaser that is a Canadian corporation, the seller may be able to take advantage of tax deferrals or “rollovers”. A purchaser may wish to utilize a target’s non-capital tax-loss carry-forwards (i.e. business losses), which can only occur through purchasing the shares of the target.

Disadvantages

A share purchase can be disadvantageous to a potential purchaser in the following ways:

A share purchase can be disadvantageous to a seller in the following ways:

A share purchase will also generally result in a “change of control” of the target that triggers a year-end for tax purposes, requiring the target to file a tax return. Additional federal income tax rules apply to restrict the use of capital and non-capital losses upon a change of control, whereby, for example: (i) non-capital losses can only be used to offset future income from the same or similar business that generated them in the first place; and (ii) capital losses generally expire on a change of control. Accordingly, share purchases often involve a review of available tax elections to gross up the tax cost of capital assets of the target.

Main Documentary Requirements

Asset Purchase Agreements

Overview and General Utilization

In an asset purchase agreement, the purchaser will acquire specific assets and rights from the target seller and therefore assume responsibility for only certain liabilities. The parties to the transaction will negotiate which assets, rights and liabilities are purchased, keeping in mind that such assets, rights and liabilities must generally be able to function as a single unit to enable the target to keep running the business post-closing. The purchaser can therefore be selective in choosing which assets to buy and liabilities to assume. The seller will remain the legal owner of the company, if applicable, which may continue operating a separate business unit or be dissolved.

Some items that are commonly acquired in an asset purchase transaction include: business information, goodwill, information technology systems, IP rights, licences, personal and real property, and stock or inventory. Consideration will also be given to which employees are offered employment by the purchaser, who will be responsible for any severance liabilities, and how employee benefit plans are transferred/assumed.

Certain liabilities will nevertheless follow the assets to the new owner and, by operation of law, cannot be contracted out of. Most typically, these include environmental liabilities associated with real property, or collective agreements relating to unionized employees.

Advantages

An asset purchase can be advantageous to a potential purchaser in the following ways:

An asset purchase can be advantageous to a potential seller in the following ways:

An asset purchase is generally more advantageous to the purchaser from a tax perspective, because it receives the full cost base in the acquired assets which normally increases available deductions for depreciable assets and reduces gains on the subsequent sale of the assets. For non-resident purchasers, additional considerations will apply when structuring the transaction, for example in moving assets to/from Canadian versus foreign affiliates. In a share purchase, it may not be possible for a non-resident buyer to move assets out of the Canadian company post-closing without triggering Canadian tax.

From the seller’s perspective, an asset purchase may be preferable to enable the target seller to generate income or capital gains from the sale of assets that can be sheltered by utilizing any significant tax-loss carry-forwards it may have accumulated.

Disadvantages

An asset purchase can be disadvantageous to a potential purchaser in the following ways:

An asset purchase can be disadvantageous to a potential seller in the following ways:

Main Documentary Requirements

Asset purchases also involve allocating the purchase price among the various assets being sold, which is important from an income tax perspective given the deductibility of various types of assets.

General Timeline

*Since the duration of share and asset purchase transactions can greatly vary depending on the circumstances and size of the deal, only a general process has been provided below. The parties and their legal advisors will also have to consider what third party consents, if any, would be required, as often certain regulatory licenses and permits, and certain contracts, including loan agreements, may contain restrictions on changes of control.

Amalgamations

Overview and General Utilization

While amalgamations are often stated to be the Canadian equivalent of a merger in the United States, it is important to note that there are key differences between the two concepts. Amalgamations are a means of combining two or more incorporated businesses, known as the predecessor corporations, into one overarching business, known as the successor corporation or Amalco. In Canada, when the predecessor corporations combine, neither is formally dissolved. Rather, they simply continue to exist as one amalgamated corporation which shares each predecessor corporation’s assets, rights, liabilities and histories.

Amalgamations in Canada can take two forms, one being a long-form amalgamation (which occurs between arms-length companies and will require a shareholder vote) and the other being a short-form amalgamation (which occurs between related companies and can usually be approved through directors’ resolutions). One unique consideration is that since amalgamations in Canada are governed by statute, the predecessor corporations must be incorporated under the same statute, meaning that if one predecessor corporation is incorporated provincially while the other predecessor corporation is incorporated federally, then one of the corporations must file a certificate of continuance under the other’s statute. While amalgamations are not unheard of in the private context, typically when a target company has a large number of shareholders making it impractical to proceed by way of share purchase agreement, they are much more commonly used in the public context.

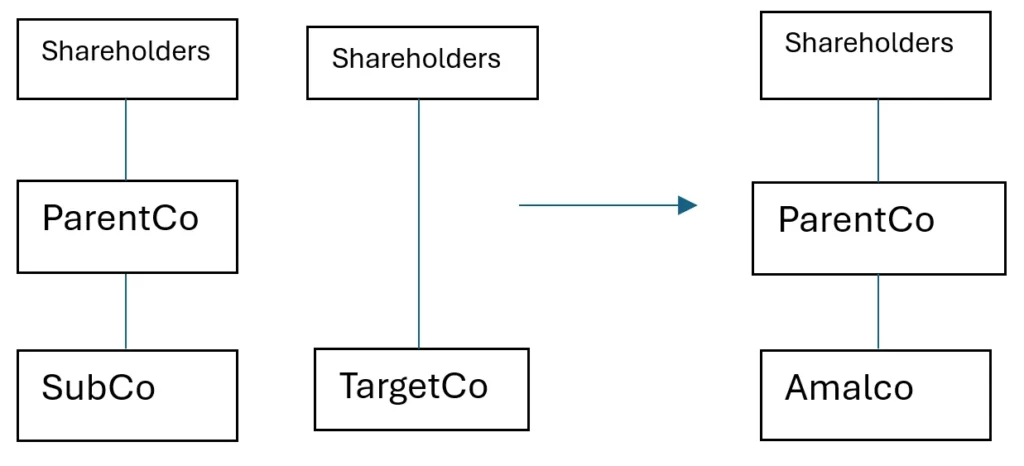

Three-Cornered Amalgamations

A triangular or three-cornered amalgamation can be used to effect an acquisition using consideration comprised of shares, or a combination of cash and shares. It is frequently utilized as an alternative to the takeover bid process under securities laws. For example, if a Canadian public corporation (ParentCo) wants to acquire the shares of another Canadian corporation (TargetCo) for share consideration, the transaction could be structured as: (i) a share-for-share takeover bid, (ii) a standard amalgamation of ParentCo and TargetCo, or as a triangular amalgamation of a subsidiary of ParentCo (SubCo) and TargetCo where TargetCo shareholders receive shares of ParentCo instead of shares of the amalgamated corporation (Amalco). In this case, ParentCo controls Amalco immediately following the amalgamation.

Using an amalgamation in the takeover context allows for the ability to implement the transaction with a two-thirds approval threshold of the votes cast at a shareholders’ meeting. Under a formal takeover bid, the acquiror would have to rely initially on tenders to the offer, and meet the thresholds of tenders to implement the compulsory squeeze-out provisions of corporate law to acquire any non-tendered shares, as discussed below.

Compared with a standard amalgamation, which requires the approval of shareholders of both ParentCo and TargetCo, a three-cornered amalgamation will not ordinarily require the approval of ParentCo shareholders, unless stock exchange policies so require it. This structure would also normally allow selling shareholders to obtain tax-deferred rollover treatment, if certain conditions under applicable tax law are met.

Advantages

The most notable advantage of amalgamations is that they are generally considered to be tax neutral. Section 87 of the Income Tax Act (Canada) states that amalgamating businesses can transfer tax attributes such as tax credits and capital losses to the successor corporation, thereby maintaining any tax advantages already existing. Further, since the assets of the predecessor corporations naturally flow to the successor corporation, rather than through a formal acquisition or purchase of assets, no immediate tax liability nor transfer taxes are triggered.

Disadvantages

The disadvantages of amalgamations are usually context specific. For example, if two major public corporations who are in the same industry amalgamate, then there may be a risk of forming a monopoly, which may triggers anti-trust legislation. Further, the successor corporation will maintain all liabilities, debts and obligations of the predecessor corporations even after amalgamation.

Amalgamations requiring shareholder approval may also operate on a lengthier timeline if a large number of shareholders need to be canvassed in order to obtain the necessary support. Each applicable corporate statute provides the necessary shareholder approval threshold for completing an amalgamation, which is at least over 50%, which threshold may increase given the provisions of applicable shareholder agreements or rights attributed to other share classes, such as preferred shares. Support agreements are often utilized in order to ensure the parties that the requisite shareholder approval will be satisfied. Timing may typically proceed faster in a private company context, as the corporate charter documents normally allow for a compressed notice period for a shareholders’ meeting, whereas in the public company context additional securities laws apply given the search processes involved in order to determine who the shareholders who are entitled to vote are as of a given record date.

General Timeline

The timeline below assumes a longer notice period prior to a meeting of the shareholders.

Main Documentary Requirements

Usefulness of Valuations and Opinions

Whether a valuation is required will depend on the specific circumstances of the amalgamation. Where not required by law, valuations may be useful to validate the consideration offered and mitigate the risk of shareholder exercising their rights of dissent. If one is required (for example in related party transactions), it must be obtained before sending the proxy circular to shareholders and it must be sent along with the proxy circular. The directors of the target company may also choose to obtain a fairness opinion from their independent financial advisors inquiring into what is the appropriate consideration for its shareholders under the amalgamation.

Plans of Arrangement

Overview and General utilization

A plan of arrangement is a flexible structuring tool commonly used in Canadian mergers and acquisitions, particularly in the public company context. It is a court-supervised statutory process that gives companies the ability to accomplish a variety of “fundamental changes” such as a reorganization, a merger with another company, or an exchange of assets, all in a single step under the procedures found in the Canada Business Corporations Act or its equivalent provincial legislations. The reasoning behind choosing a plan of arrangement generally involves a need to make significant changes to corporate structure in order to maintain fairness to the shareholders whose rights may be affected in a complex merger. Once a definitive agreement is reached between the bidder and the target company, the plan of arrangement will require both majority shareholder approval (typically approval by holders of 66 2/3% of the outstanding shares) and court approval before being effectuated. The court approval process ensures the transaction is binding on all securityholders, even dissenters and, in some instances, creditors, where the court order approving the arrangement confirms the plan is fair and reasonable to all parties involved.

While more commonly used for public companies, plans of arrangement are being increasingly utilized in the private sphere for companies which have a large number of shareholders.

Advantages

Plans of arrangement can deal with multiple aspects of a deal, such as tax planning or addressing multiple classes of securities, all in one step, making it a more efficient process. Additionally, arrangements provide the greatest amount of flexibility to the parties involved, especially if certain securityholders of the target will need to be be compromised or otherwise have their rights modified, and can be customized to address the specific goals at hand. If applicable, there are some advantages to U.S. acquirors who obtain securities pursuant to plans of arrangement as they will be exempt from registering their securities with the SEC due to plans of arrangement being considered corporate-level transactions instead of formal tender offers under U.S. securities laws.

Disadvantages

Given that there is a level of judicial discretion involved as court approval is required, parties must prepare their materials with a view to satisfying the court that the arrangement serves a valid business purpose, is fair and reasonable to securityholders and responds adequately to those whose rights are being affected. As a result, the use of fairness opinions or valuations become more relevant as tools to validate the offer. This court process also gives unsatisfied securityholders a platform to voice their objections, which can cause delay or the ultimate failure of the transaction. Further, the need for both shareholder and court approval means that plans of arrangement can require longer timelines to complete, especially as these transactions will need more fulsome disclosures to be prepared. Those on the acquiror/bidder side should keep in mind that plans of arrangement are a target-driven process and thus, the acquiror will have limited control over the timing and preparation of documents (compared to, for example, a take-over bid made by the acquiror directly to the target’s shareholders).

General timeline

Main Documentary Requirements

Usefulness of Valuations and Opinions

While not a set requirement, courts generally have an expectation that a valuation and a fairness opinion from the target’s independent advisors will be included in the materials submitted to court in asking for their approval. Such documents, if applicable, will be sent to shareholders along with the proxy circular.

Take-over Bid

Overview and General Utilization

A take-over bid will be triggered when an offer is made from an acquiror directly to the shareholders of the target to acquire voting or equity securities of a class where the securities implicated (in addition to any securities already beneficially owned by the acquiror and its affiliates, if any) will constitute 20% or more of all outstanding securities of the class. In measuring what constitutes 20% ownership, acquirors must include all securities that it beneficially owns or has control over as well as any securities that the acquiror has a right to acquire within 60 days, such as options.

Once the 20% threshold is reached, take-over bid rules will be triggered such as mandating the acquiror to make the same offer to all of the target’s shareholders with identical consideration and no collateral side agreements, absent any exemptions. Other rules that will be triggered include the mandatory bid period timeline where the bid must be open for 105 days, which may be shortened to a minimum of 35 days at the discretion of the target, as well as the minimum tender condition whereby more than 50% of securities owned by persons other than the acquiror must be tendered to the bid before the acquiror may take up any securities under the bid.

Take-over bids are typically used to acquire public companies and can take either a friendly or hostile form, as will be discussed below. This type of transaction is often considered the Canadian equivalent to a U.S. tender offer. Take-over bids technically also apply to offers made for the shares of a private company, but most acquirors in this context would be able to avail themselves of applicable exemptions to the formal bid requirements under Canadian securities law. Take-over bids may also be a preferred option in the context of private company acquisitions where there is a large shareholder base and valuations may be complicated or prohibitively expensive. In the private company context, the acquiror would seek exemptive relief from securities regulators to avoid the application of the formal take-over bid rules, in particular if it intends to use its own shares as consideration.

Advantages

This process is the only one available for unsolicited or “hostile” bids, meaning that the agreement of the target itself is not required and the acquiror can force an acquisition through negotiations with the shareholders of the target.

Despite the 105-day minimum offer period, take-over bids can potentially be completed much faster, particularly if the transaction is friendly, as the target board may waive the minimum period to as short as 35 days.

For the acquiror, a take-over bid can give them more control compared to other forms of acquisitions given that the acquiror is the one who determines the initial bid price and the timing of the launching of the transaction.

Disadvantages

A second-step transaction may be required to gain 100% ownership of the target if the acquiror is unable to obtain at least 90% of the target’s securities in the initial bid.

If the take-over is hostile, then the transaction may take significantly longer to complete than other acquisition transactions.

A hostile target board can recommend to their shareholders to reject the take-over bid and in general, utilize a variety of defence tactics to make the entire transaction a more difficult process (for example, in providing access to due diligence documents).

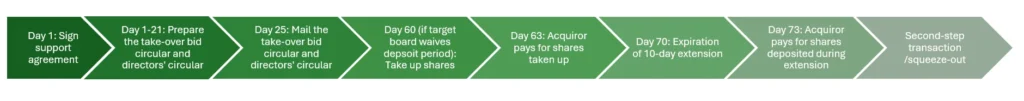

General timeline

Hostile

Friendly

Main Documentary Requirements

In the public company context, a bid whereby the acquiror offers its own shares as consideration will be subject to prospectus-level disclosure in its offering documents, which makes the preparation of the circular a more complex process.

Valuation

The acquiror may be required to include a valuation of the public company target performed by an independent party in its disclosure materials.

Due Diligence

No matter which acquisition process is chosen, due diligence by the acquiror will be essential to a successful transaction. Generally, the acquiror should review the target business’ assets and liabilities, corporate documents and contracts, and conduct the applicable corporate and other searches (claims, personal property security registrations, employment, tax and bankruptcy searches, etc.). The extent of the due diligence will depend on a variety of factors including, among other thins, the circumstances of the transaction, the complexity of the transaction, the nature of the business, whether it is a private or public acquisition, and the time available.

Financing

In the business transactions discussed, except for take-over bids, there are no regulatory requirements on financing. Either cash or shares can be offered as consideration with plans of arrangement offering the greatest flexibility on consideration arrangements. With that said, target companies may have an expectation that the acquiror can show some evidence of being able to finance the transaction.

In a take-over bid, if the consideration given for the transaction (or part of it) is cash, then there is a rule that these bids must be fully financed by the acquiror before the bid is launched. If the financing itself is conditional at the commencement of the bid, the acquiror must reasonably believe that the possibility that it will be unable to pay for securities deposited under the bid is remote.

Controlled Auctions

A controlled auction is a way for the target company to sell its business by soliciting bids from acquirors in a process that the target controls. Sellers tend to resort to controlled auctions when they wish to obtain a high sale price for the target by attracting a large pool of bidders. This can be an attractive option for private companies if they have organized leadership and the business is in proper order before commencing with the auction process.

A controlled auction may entail the following steps:

Toe-hold Acquisitions

Toe-hold acquisitions are a means by which acquirors can accumulate some shares of the target company (under 20%) before announcing their intention to make a take-over bid. There are multiple reasons for acquirors choosing to undergo this procedure including: (i) it can lower the overall purchase price of the target as the acquiror avoids paying a premium for the shares purchased prior to the take-over bid; (ii) the acquiror can use their position within the target company to gain an edge against a competitive bidder; and (iii) it may allow the acquiror to position themselves advantageously within the target’s management team prior to making a formal bid.

While an attractive strategy for acquirors, they should note that if their holdings within a public company target reach 10%, a number of rules are triggered such as having to publicly disclose their shareholdings. This kind of tip-off may increase the market price of the target’s shares and erase any benefit gained in avoiding the bid premium. Additionally, subject to some exemptions, the highest price an acquiror pays for the shares of the target within 90 days of launching a take-over bid will be the lowest price the acquiror can then offer in their take-over bid. The shares acquired through the toe-hold will also not assist the acquiror in meeting the 50% minimum tender condition nor the 90% compulsory acquisition threshold in their eventual take-over bid as these pre-acquired shares are not counted.

Lock-Up Agreements

An acquiror can enter into a lock-up agreement with shareholders (often major shareholders) of the target whereby those shareholders agree to tender their securities to the acquiror’s offer or vote in support of the transaction. These agreements help acquirors reach higher levels of certainty in completing the transaction successfully, such as in reaching the 50% minimum tender condition in a take-over bid. These agreements can either take the form of a “hard” lock-up or a “soft” lock-up. In “hard” lockups, the shareholder cannot withdraw their securities and/or support in favour of another potential buyer until a set time period expires. In “soft” lock-ups, the agreement will terminate if the target chooses to go with a competitor’s superior offer, which will allow the locked-up shareholder to support the superior offer. Most lock-up agreements in Canada are “soft” lock-ups.

Overview

Amalgamations and plans of arrangement are considered friendly acquisitions as the transaction is completed with the cooperation and agreement of the target company’s board of directors. Take-over bids can be friendly or hostile depending on whether the bid is unsolicited or not. In the friendly approach, a buyer will submit a letter of intent and the parties will determine which form of acquisition is most compatible with their goals. Agreements such as standstill agreements, where the buyer agrees to not launch a hostile take-over of the target for a certain period of time, and break fee agreements, where the acquiror is given a fee if the target’s shares end up being purchased by a competing buyer, are common agreements made in friendly take-overs. In a hostile take-over, the buyer will make an offer directly to the shareholders of the target either after their offer is rejected by the target’s board or with no prior interaction with the target or their board at all.

The Target Board

Obtaining the support of the target’s board can be important in increasing the likelihood of a successful acquisition due to reasons such as greater access to confidential documents and due diligence documents as well as more general cooperation and heightened certainty of successfully consummating the deal.

The relevance of the target board can have some influence before the courts as the directors of a company have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the company and thus, if the transaction requires court approval or some aspect of the transaction lands before the courts, a certain level of deference and consideration will likely be given to the judgment of the directors, provided that such judgment is seen as reasonable and in the best interests of the company, .

Due to the nature of a hostile take-over, the target board will often be completely replaced upon a successful take-over.

Effect of Choice

Acquirors who choose to undergo the hostile take-over process should prepare themselves for a lengthy transaction and understand that their due diligence of the target company may be limited to only publicly available information. On the other hand, acquirors who choose the friendly route should be prepared to sign standstill agreements and understand the limitations on their actions resulting from such agreements.

Squeeze-out mechanisms are used when an acquiror seeks to obtain 100% ownership of the target and has found themselves unable to accomplish this through the take-over bid process.

Second-step business combination

The first method to obtain the remaining shares of the target is a second-step transaction/going-private transaction. When a take-over bid results in at least 90% of the shares of the target being tendered to the bid, the acquiror is often able to force the remaining 10% into a compulsory acquisition to gain 100% ownership by operation of corporate law. However, when fewer than 90% of the target’s shares are tended, the acquiror may have to enter into a second-step business combination transaction no later than 120 days after the expiry of the bid in order to “squeeze out” the remaining minority shareholders. The second-step transaction will typically require approval by holders of two-thirds of the target’s shares where the acquiror, as the majority shareholder, can vote with their newly acquired shares to ensure that the approval is a foregone conclusion. The actual form of the second-step transaction will often be an amalgamation, a plan of arrangement or a reorganization of some kind.

Compulsory Acquisition

As mentioned, if the acquiror is able to obtain 90% of the shares of the target in their bid within 120 days of the commencement of the bid, that will allow the acquiror to purchase the remaining outstanding shares for the same price offered under the bid pursuant to “compulsory acquisition” provisions under relevant corporate statutes. Minority shareholders which did not tender to the bid maintain rights to apply to a court and dissent about the fair value of their shares.

Confidentiality/Non-Disclosure Agreement

Non-disclosure agreements are most often entered into pursuant to a friendly take-over bid, whereby the acquiror is prevented from approaching the target’s shareholders directly without permission from the target board. Notwithstanding its use in take-over bids, non-disclosure agreements are commonly employed in all sorts of transactions where the parties involved do not want some aspect of the deal or their interactions with each other to be revealed to third parties.

Letter of Intent

A letter of intent or term sheet will detail the basic terms of the transaction and can include both binding and non-binding terms.

Common terms may deal with aspects such as: due diligence, public announcements, confidentiality provisions, allocation of expenses, price/consideration, payment method and terms, representations and warranties, and conditions to closing.

Considering the vast amount of litigation which has been conducted on whether a certain provision in the letter of intent is binding or not, it is advisable for parties to explicitly state in their letter of intent whether specific provisions are meant to be binding or not.

Purchase Agreement

All of the transactions discussed will require a definitive agreement or offering document which outlines the terms of the deal in greater detail. These agreements will typically include provisions dealing with: the purchase itself including the price, consideration and post-closing adjustments, escrow, representations and warranties of all parties and their respective lengths of survival, the conditions of all parties, a list of documents to be delivered to the other party and indemnities, if any.

Escrow Agreement/Holdbacks

It is common for negotiated deals in Canadian M&A transactions for a purchaser to hold back part of the purchase price to cover any post-closing adjustments or indemnity claims. The usual process for this is for the buyer to pay the holdback amount to an escrow agent, often one of the parties’ legal counsel, who will hold the amount for a set amount of time. If there is an expectation of a price adjustment post-closing or if there are any concerns about a target company’s financials or alleged assets, the holdback will allow the buyer to more easily recover amounts that are due to them.

Support Agreements

Support agreements can be found in both friendly and hostile acquisitions. As already mentioned, in friendly acquisitions, support agreements can be entered into with either shareholders or the directors and management team of the target so that such individuals vote in favour of the transaction. This support can help ensure certainty of the success of the transaction or even provide some relief to a potential buyer who ends up losing out on the deal to a third party with a superior offer (through a break fee provision). In a hostile take-over, a support agreement may eventually be drafted between the acquiror and the target board as a negotiating piece for an increase in the consideration offered for the deal.

Common terms in a support agreement can include: an agreement to carry on business as usual and advise of any material changes, representations and warranties, obligations to the target’s employees, details around the transaction process such as mailing out proxy circulars and reorganizations, break fee provisions or reverse break fee provisions if the acquiror terminates, no-shop or go shop provisions, standstill provisions, termination rights and the identities of the target’s directors and officers post-closing.

Information Circulars

Proxy circulars, also called information circulars, are disclosure documents which contain information that must be given to shareholders before an acquisition takes place in order for the shareholders to make an informed vote on whether they are in favour of the transaction. If the terms of the deal change or important information has arisen, then updated circulars must be mailed out to all shareholders. Proxy circulars will be required if the target is a publicly traded company but are not generally needed for private company transactions.

A directors’ circular is used in a take-over bid as a way for the target board to make a recommendation either accepting, rejecting, or taking a neutral stance on the bid accompanied with their reasons for choosing so.

Representations and warranties will be found in nearly every type of definitive purchase agreement as they provide both parties with some degree of security that the due diligence is comprehensive and true in all material aspects. They can also provide parties, and particularly the buyer, with a remedy post-closing if the business was not accurately portrayed.

Generally, the representations and warranties made by the target will be more fulsome and extensive than those made by the acquiror, who usually only gives limited representations and warranties.

Common Clauses

Common representations and warranties found in Canadian acquisition agreements include provisions relating to the following:

Covenants whereby the target agrees to continue carrying on the business in the ordinary course and to avoid any action which could cause material adverse changes through to closing are also common.

Survival

Canadian transactions will typically include specific clauses stating that the representations, warranties, covenants and guarantees will survive the closing for a set period of time, usually being 1 to 2 years, which assist the purchaser in pursuing claims for liabilities discovered post-closing that arose from misrepresentations given at the time of closing.

Indemnification

A common clause found in Canadian purchase agreements is the indemnification provision which will require the buyer and the seller to compensate each other for breaching the representations, warranties and covenants made. The advantage of including an indemnification provision is that if the transaction leads to litigation, indemnities can provide parties with a level of certainty in terms of potential damages rather than leaving the consequences completely to the court’s discretion. Further, the indemnity would allow parties to predetermine a limit on the amount of damages as well as stipulate alternative remedies for certain breaches, should the parties choose.

Sandbagging

Sandbagging provisions can generally come in two forms. Pro-sandbagging provisions allow the buyer to recover for breaches of the definitive agreement which the buyer knew about prior to closing. This type of provision will essentially state that the buyer’s right to indemnification, payment, remedy, etc., will be maintained despite any knowledge acquired before closing in regards to the accuracy of the representations and warranties made.

The other form of a sandbagging provision is an anti-sandbagging provision, which would provide the seller with a defence against claims of misrepresentation by the buyer if the buyer knew about the misrepresentation but still proceeded to close. This type of provision may state that neither party will be liable for losses relating to a breach of the representations and warranties made if the claiming party knew of such breaches before closing.

Another alternative is that definitive agreements may be silent on sandbagging altogether. Canadian agreements do not typically include a sandbagging provision and the existing jurisprudence seems to suggest that a pro-sandbagging interpretation will be favoured by the courts if the agreement is silent. These types of provisions are often considered in the context of extensive indemnities or other exposure by the sellers post-closing.

Directors’ Duties

Key Fiduciary Duties

The key directors’ duties in Canada mainly revolve around the following statutory duties:

The directors of a company are responsible for the overall management of the company. In performing these duties, directors must consider what course of action is in the best interests of the company and in doing so, directors should be familiar with all material information that could affect the company.

Directors have a duty of care towards the company in that they must act in a way that is reasonably expected of a person in their position, with all the diligence and skill that would be expected of someone in that position. With that said, courts do not impose the standard of perfection on directors. Instead, courts more often look to whether the directors have acted honestly, prudently and in good faith in discharging their duties. In order to satisfy this duty of care and protect themselves from liability, directors must ensure that their actions can be seen as reasonable – that it is within the realm of possibility that someone in their position with their level of knowledge could potentially come to the same conclusions based on the facts of the matter.

Directors have a fiduciary duty to always act with a view to the best interests of the company such that they must ensure they do not allow a personal interest or a competing interest to cloud their judgment. Thus, there are often requirements surrounding the full disclosure of any material conflicts of interest which may arise regarding the directors’ relationship with other companies that they are involved with. Directors owe this fiduciary duty to the company itself and not to the shareholders of the company, even though it is accepted that some shareholders may inadvertently benefit from the decision that is in the best interests of the company. Further, directors may take into account the effects of certain decisions on the shareholders as one of many considerations as to what is best for the company. As mentioned earlier, the standard imposed on directors is not the standard of perfection but of reasonableness.

Special/Independent Committees

An independent committee, also known as special committee, is a temporary group comprised of directors of the target company who are independent/have no conflicts in connection with a proposed transaction. The committees are formed with the purpose of evaluating and advising on the terms of a transaction from an impartial viewpoint. They are often asked to provide a recommendation to the board of directors about the proposed transaction. If the independent committee has performed its role in good faith and the board has acted on the committee’s recommendation, that decision will generally be given judicial deference from the courts.

While not always a requirement, establishing an independent committee can be important to show that the board’s decision was made conflict-free. Some securities regulators will require independent committees for certain types of transactions, such as insider bids.

Business Judgment Rule

The business judgment rule is a concept applied in courts whereby judges will give judicial deference to the business decisions of a board of directors when asked to review whether the board acted appropriately. That is, courts will not expect a board of directors to make perfect decisions for the company all the time. As long as the board had a reasonable basis for making that business decision, and in the absence of any fraud, illegality or conflict of interest, courts will generally not usurp the board’s authority to manage the company. If the business decision was within the reasonable range of possible decisions that could have been made and it was made honestly and in good faith, the courts will not substitute their own opinion for the board’s opinion.

However, boards of directors should be prepared to show evidence that their decision was the result of sound, logical and thorough reasoning as the business judgment rule is not meant to give a board unfettered discretion.

Conflicts of Interest

Many Canadian corporate statutes contain provisions dealing with conflicts of interest. If a director or officer involved in a business transaction has a material interest in the other party to the transaction, the director will be required to disclose the full extent of their interest. Oftentimes, if such a conflict of interest exists, the director or officer involved will be required to refrain from voting on that transaction. Conflicts of interest frequently become the subject of litigation in Canadian law such that it would be prudent for boards of directors to be clear on where the law in Canada currently stands in terms of what is and what is not considered a material conflict.

Oppression Remedy

Most Canadian corporate statutes permit shareholders, holders of debt obligations and other appropriate complainants to claim an oppression remedy in court. The oppression remedy allows courts to determine if there have been actions taken within the company which have been oppressive against, unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly disregards any shareholder, creditor, director, or officer. If oppression has been made out, the court then has the authority to make any order it deems fit, whether interim or final, to remedy the oppression, including ordering majority shareholders to buy out the minority shareholders’ stake in the company at fair market value. Whether oppression has been made out or not will depend on the reasonable expectations of the complainant. For example, did the company protect the interests which the complainant reasonably expected it to protect?

Due to the broad and sweeping authority given to courts in choosing how to fix the alleged oppression, the oppression remedy is a powerful legal tool for complainants.

Can a Target Resist?

In a hostile take-over bid, the target company may find itself trying to defend against the take-over using a variety of methods available to it. However, Canadian securities regulators can take action where the defensive measures used are likely to deny or severely limit the ability of shareholders to respond to a take-over bid.

Shareholder Rights Plans

Shareholder rights plans, also known as “poison pills”, are a defensive tactic to prevent hostile take-over bids. Generally, they provide existing shareholders with the right to buy additional shares at an extreme discount when an acquiror reaches the 20% threshold to trigger a take-over. This effectively dilutes the shares of the acquiror, thereby making the take-over harder to implement.

Prior to 2016, when the minimum bid period was 35 days, the main purpose of such shareholder rights plans was to extend the time the target board would have before the take-over was complete, in order for them to think of alternatives. In 2016, the minimum bid period was amended to 105 days, thus neutralizing the utility of such plans. Nevertheless, shareholder rights plans continue to be used by public companies given that they remain an effective way to prevent certain creeping take-overs.

Private Placements

In short, private placements occur when an issuer offers securities privately (i.e. not a public offering) to accredited investors in order to prevent or deter a hostile take-over. However, companies who choose to use private placements as a defence tactic should be aware that Canadian securities regulators can intervene if they find the private placement has completely frustrated the ability of shareholders to respond to the take-over bid or competing bids. Regulators will consider if the importance of investor protections outweighs the target board’s judgment.

Restructuring

A target company facing a hostile take-over may attempt to restructure the business by selling off a significant asset in order to provide its shareholders with cash and thus becoming less attractive to bidders. However, this type of transaction must have a demonstrable business purpose with a view to the best interests of the company. If the target board is unable to defend their decision to restructure, then the sale of the asset could risk being set aside by the court.

Alternatively, a target board can choose to recapitalize the company by substantially increasing long-term debt along with a concurrent declaration of special dividends to provide cash to shareholders.

White Knight

A white knight transaction occurs when the target company undergoes an alternative transaction with a friendly party on terms that may provide increased value to the target or more preferential terms to the target’s shareholders.

Advance Notice By-Laws

Advance notice by-laws can be implemented into a company’s Articles or other constating documents which will require that shareholders provide a formal notice within a prescribed time window if they want to propose new nominees to the board of directors. This ensures that the target’s board will have enough time to sufficiently evaluate the proposed directors and give the board more time to strategically respond to proxy fights.

Acquiring Assets

Acquiring a significant asset can make a target company less attractive to bidders by increasing the cost of the transaction or possibly attracting antitrust problems for the bidder if the take-over were to succeed. Similar to a restructuring, there must be a demonstrable business purpose for the asset acquisition and it must be reasonably believable that the acquisition was in the best interests of the company and not for the sole purpose of defending against a hostile take-over.

Just Saying “No”

Considering the purpose and process of hostile take-overs, it is not accepted in Canada for target boards to “just say no” to a bid. However, what boards can do is try to convince their shareholders to reject the bid and not tender their shares because the bid is not in their best interests.

Certain Canadian securities regulators, as well as most stock exchanges in Canada, specifically regulate the transaction processes for the following four types of transactions: insider bids, issuer bids, business combinations and related party transactions. These four transactions have been singled out as regulators recognize that these transactions can be result in unfair consequences for minority shareholders. Multilateral Instrument 61-101 – Protection of Minority Security Holders in Special Transactions (“MI 61-101”), for example, has implemented procedural safeguards, such as valuations, minority shareholder approval and disclosure requirements, in an attempt to maintain equal treatment of all shareholders.

Insider Bids

Insider bids are take-over bids initiated by an existing stakeholder of the company, such as a director, senior officer, major shareholder with at least 10% of all outstanding shares or any affiliated entity of the company.

These types of bids will trigger regulatory requirements under MI 61-101, in that the offeror, at their own expense, must deliver to shareholders a formal valuation prepared by an independent valuator. An independent committee will be required to advise on the transaction and take on roles such as choosing the valuator, supervising the preparation of the valuation and overseeing timelines. Prior formal valuations of the company within the last 24 months must be included in the disclosure sent to shareholders. The details of any bona fide prior offers to the company received in the last 24 months must also be disclosed in the circular.

Issuer Bids

An issuer bid is an offer to acquire or redeem securities of an issuer by the issuer itself in an attempt to reduce the number of outstanding shares of the company. It is essentially a buy-back of the shares and it will be triggered regardless of the number of shares repurchased, unless exemptions are available. Generally, an issuer must provide a formal valuation, prepared by an independent valuator, to its shareholders as well as a disclosure which includes information about every prior valuation, the details of the issuer bid, a statement of the intention, and of the effect of the issuer bid on the voting interest of all interested parties, just to name a few.

Related Party Transactions

A transaction between an issuer and any person, other than a bona fide lender, that is a related party of the issuer falls under the umbrella of a “Related Party Transaction”. By way of example, these related parties can range from major shareholders who manage the operations of the issuer to a subsidiary or affiliate of the issuer. Essentially all types of transactions, whether borrowing, lending, acquisition or asset sales, will be subject to the requirements of MI 61-101 as related party transactions if the parties involved are not at arm’s length. These transactions will similarly require formal independent valuations and specific disclosure requirements, as well as minority approval (approval of a majority of the minority shareholders, not including the related party). Exemptions do exist for these requirements, such as where the fair market value of the transaction is less than 25% of the market capitalization of the issuer and where the transaction is in the ordinary course of business.

Business Combinations

Business combinations occur when a transaction involves an acquiror who obtains control of one or more businesses and includes arrangements, amalgamations, consolidations or other transactions as a means of gaining that control. Whether control has been obtained can be determined through a variety of factors such as whether the acquiror has the majority of voting rights, whether the acquiror owns most of the assets, and whether the acquiror can exercise power of the acquired company.

MI 61-101 will only apply to business combinations if the parties involved are reporting issuers (i.e. public companies). If MI 61-101 applies, the business combination transaction will typically require a formal valuation as well as “majority of the minority” approval. An independent valuator must be appointed and a formal valuation must be prepared. There are multiple exemptions from the formal valuation requirement such as if the transaction is part of a second-step transaction, or if the issuer is not listed on any stock exchange market.

Independent Formal Valuation

Any formal valuation required by MI 61-101 must be prepared by an independent valuator. MI 61-101 contains provisions which outline that a valuator will not be independent if:

MI 61-101 also provides for how the formal valuation is to be prepared and the requirements for filing the formal valuation.

Majority of Minority Vote

If minority approval is required for a business combination or related party transaction, the vote must be held in a separate class vote from the holders of every class of affected securities of the issuer. MI 61-101 further contains details about when certain votes will be excluded, which primarily deal with when the votes are attached to securities which are owned by entities related to or not at arm’s length from the issuer.

A Canadian Acquisition Vehicle

If a foreign buyer wants to acquire a Canadian target company, it is generally advisable for them to do so through a Canadian acquisition vehicle. Using a Canadian acquisition vehicle carries with it a variety of tax planning options and potential benefits such as:

Exchangeable Shares

Exchangeable shares are shares issued by a Canadian company (a subsidiary of a foreign parent acquiror) that are economically equivalent to the common shares of the foreign parent. These shares are exchangeable for the common shares of the foreign company. This structure allows the Canadian shareholders of the target company to receive payment in the form of shares in the Canadian entity instead of the foreign entity. Since the Canadian target receives shares that are issued by a Canadian company, they can defer the taxes on the capital gain that would otherwise be triggered in a share-for-share exchange.

Section 116 of the Income Tax Act

Buyers who purchase real estate, whether residential or commercial, from a non-resident of Canada should be aware of their obligation to withhold tax until the foreign Vendor presents them with a section 116 certificate from the Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”). Non-residents will be subject to Canadian income tax when they receive capital gains on “taxable Canadian property”, which can include real property and shares of companies whose assets are primarily attributable to real property.

If the foreign seller does not have other property in Canada, this makes it difficult for the CRA to enforce tax payments on the seller and thus, the Income Tax Act puts the burden on the purchaser for the seller’s capital gains tax if the seller does not pay them. When buying from a non-resident, the buyer is required to withhold 25% of the purchase price and remit it to the CRA. However, the non-resident can help the buyer avoid this 25% if the non-resident applies to the CRA for a section 116 certificate. In order to obtain the certificate, the non-resident must calculate the amount of tax payable on the capital gain and remit that amount to the CRA.

When pursuing a merger and acquisition, the parties involved should turn their minds to any privacy legislation applicable to the transaction. In Canada, there are federal privacy statutes as well as provincial statutes. Generally, these statutes will regulate the use, collection and disclosure of personal information by private (i.e. non-governmental) organizations and will require the consent of the individuals implicated for such collection, use and disclosure of their personal information.

In order to satisfy this consent requirement, some companies will be able to rely on their pre-existing privacy or consent policies while others may try to obtain consent from each relevant individual. However, recognizing the practical hurdles of obtaining consent, Canadian privacy legislation includes a business transaction exemption whereby the company can disclose personal information to third parties without obtaining consent if certain conditions are met.

Under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA”), transactions where the exemption is available will typically include: the purchase or sale of an organization or its assets; the merger or amalgamation of two or more organizations; the provision of loans or other financing; the creation of a charge or security interest on the assets of an organization, the lease or licence of any assets of an organization; or any other prescribed arrangement. There are further requirements that the parties to a transaction will need to satisfy if they intend to rely on these business transaction exemptions. Therefore, buyers and sellers must inform themselves of these conditions if they intend to rely on the exemption.

Privacy concerns are of particular importance in transactions dealing with personal health information and there are specific federal and provincial statutes which deal with the dissemination of personal heath information. It is paramount for the implications of this legislation to be considered by the transacting parties if the deal will likely involve individuals’ health information.

Employee Contracts

Share Transactions

In a share purchase, the purchaser will inherit the target company’s employees’ history and past service for all purposes as there is no legal change in employer. Thus, typically no significant change to any existing employment contract needs to be made and any employee seniority will be retained.

Asset Transactions

In an asset purchase, employment contracts are not automatically assigned to the purchaser but a change in employer may have occurred pursuant to the transaction. Therefore, the purchaser must extend offers of employment to the existing employees of the target whom they would like to retain. These offers usually encompass terms which are similar to those the employee originally had with the seller. While not required to be exactly on the same terms and conditions, any changes the purchaser makes to the conditions of employment must be comparable, in the aggregate, to the prior terms and conditions.

Employees are not obligated to accept the new employment offer and if they do not, they will be deemed to remain as the seller’s employees. It is then the seller’s responsibility to terminate these employees. Upon termination, employees will have a duty to mitigate their losses such that they must make a genuine effort to seek alternative employment. In the context of an asset sale, accepting the purchaser’s employment offer would be seen as part of the duty to mitigate if the offer was reasonable. Thus, a terminated employee who did not accept the employment offer may lose their ability to claim for damages pursuant to the common law.

In terms of seniority, multiple provinces have in place legislation which deems an employees’ employment to not have been terminated if it was pursuant to a sale of business. If the employee accepts the offer of employment, then their employment history will be deemed to continue uninterrupted such that seniority is retained. Employers should note that they cannot contract out of these legislative provisions.

Canada Pension Plan

Despite legislation deeming that employment is uninterrupted in an asset purchase, under the Canada Pension Plan (“CPP”), the purchaser will still be considered a new employer for the purposes of the contributions required. This designation means that the purchaser will be required to mall all CPP contributions even if the seller had made all payments and deduction that year prior to closing. Therefore, parties considering an asset sale should bear in mind how to take advantage of timing to no overpay in CPP contributions.

Workplace Safety

Some provincial workers compensation legislation, such as those in Ontario and Québec, will have provisions which replace a right to sue an employer with a statutory compensation fund. In an asset transaction, the purchaser will want to consider the seller’s record under these legislations as it is the purchaser who will inherit this record and the record itself determines the level of payments an employer will be subject to. It is also the purchaser who will take on all remaining payments due and owing under these legislations. Thus, it is advisable for a purchaser to make this a point of due diligence.

Primary Regulators

The primary regulators of mergers and acquisitions in Canada are:

Reporting issuers must comply with the disclosure requirements and file the necessary documents on SEDAR+ while reporting insiders, which include major shareholders of minimum 10% of a class of securities, must file trade reports on SEDI, subject to any exemptions.

While there is no single national securities regulator in Canada, there has been fairly successful effort to harmonize the provisions of all securities regulators in Canada.

Foreign Investment Restrictions

Under the Investment Canada Act (“ICA”), the Canadian government maintains the right to block proposed foreign investments of significance or place certain conditions on these investments at their discretion. A direct acquisition which results in the control of Canadian businesses by foreign investors (who are in a World Trade Organization country) will require a review if the enterprise value of the target business exceeds Cdn$1.386 billion. This threshold value applies for most kinds of transactions unless it involves an acquisition of a cultural business, an acquisition by a non-WTO investor or direct acquisition by a state-owned enterprise, each of which have different monetary thresholds which trigger review. Upon review, the foreign entity must prove to the Canadian government that the transaction will result in a “net benefit” to Canada.

Even if a transaction is not reviewable under the ICA because it does not reach the monetary thresholds, there is still a mandatory requirement that a notification be filed anytime pre-closing or within 30 days after the transaction has closed.

National security reviews can be conducted under the ICA regardless of whether the investment exceeds the monetary threshold or not. A transaction will undergo a national security review where there is potential for it to be injurious to national security. State-owned-enterprise investors will likely be subject to such reviews.

Antitrust Regulations and the Competition Act

Foreign investments are also subject to pre-merger notifications under the federal Competition Act if they meet certain financial and voting interest thresholds. To be notifiable, the transaction must exceed both of the following thresholds:

If the transaction concerns the acquisition of voting shares, it will be notifiable if the investor’s voting interest post-closing exceeds 20% for a public company, or 35% for a private company. If the investor already exceeds those thresholds prior to the transaction, then notification will be required if their voting interest increases to 50% post-closing.

Regardless of whether these thresholds are reached, the Competition Bureau reserves the right to review any transaction within one year of its closing in order to determine whether the transaction is likely to substantially lessen or prevent competition in Canada.

Courts

Traditional litigation is a common and longstanding method for dispute resolution in Canadian mergers and acquisitions. Most, if not all, definitive agreements will include a provision which designates the courts of a Canadian province as the forum, exclusive or non-exclusive, for any litigation proceedings resulting from the transaction.

Arbitration

Arbitration is an increasingly popular method of dispute resolution in Canada as it usually brings benefits such as lower costs, faster resolution speeds, and flexibility in negotiating terms amenable to all parties. While not a requirement, it is usually advisable for cross-border transactions to include an arbitration clause in their definitive agreement in order to avoid being subject to an undesirable court jurisdiction. However, parties should note that arbitration in Canada may have limited appeal options and there is often a high level of deference given to the arbitrator’s decision.

Ally Law is not a law firm. By providing information to Ally Law through this website or otherwise communicating information to Ally Law, you are not establishing an attorney-client relationship with Ally Law or with any independent local firms that participate in Ally Law. The information you provide us will not be afforded legal protection as an attorney-client communication. This means that while Ally Law will protect the confidentiality in accordance with the policy described above, the information you provide is not protected under the laws relating to attorney-client privilege, and Ally Law may be compelled to disclose information you provide in certain legal proceedings. Accordingly, you should not provide any information concerning your legal needs you wish to be protected by attorney-client privilege.

505 Burrard St #1100,

Vancouver, BC V7X 1M5,

Canada

Call: +1 604 331 8300

Jordan E. Langlois

Partner

Email: jlanglois@kornfeldllp.com

Call: +1 604 331 8320

Mihai H. Ionescu

Partner

Email: mionescu@kornfeldllp.com

Call: +1 604 331 8318

Catherine Yue

Associate

Email: cyue@kornfeldllp.com

Call: +1 604 331 8369